Morganite

featured newsMorganite is a pinkish form of beryl. The beryl group of gemstones contains some of the most highly desired and more expensive of the coloured gems – the most famous of which is emerald – with a wide variety of colours represented, ranging from colourless to black.

Image supplied by Rebecca Sampson, Tallulah.

Beryl is a silicate of beryllium and aluminium, with a hardness of 7.5 to 8 on Mohs’ scale. Beryl crystallises in the hexagonal crystal system and is a doubly refracting gemstone (uniaxial negative).

The use of beryl as a gemstone dates back more than 5,000 years, when they were sold in the markets of the ancient city of Babylon.

Emerald is regarded as one of the most desirable beryl gemstones, closely followed by aquamarine, and more recently, morganite (pink beryl) and heliodor (golden beryl) have also become popular for use in jewellery.

Today, we will focus on morganite. Morganite was only discovered in 1910 in Madagascar and was at first simply called ‘rose beryl’ due to its colour, which can range from pale pink to orange-pink and deeper pinkish purple to intense pink, while exhibiting distinct pleochroism.

George Kunz, the chief gemmologist at Tiffany & Co., suggested it be renamed after New York financier JP Morgan to honour his philanthropic work.

Morgan was also one of the Western world’s most prominent collectors of gemstones in the early 20th Century.

Madagascan mines are today only minor sources of morganite, yet they still produce the best quality material.

Morganite is also mined in the Minas Gerais region of Brazil, as well as Mozambique, Namibia and the US – the latter of which has only minor and inconsistent deposits.

The colour of the gemstone due to traces of the element manganese, which can create hues ranging from pink to rose, peach and salmon.

The pinker shades of morganite are more popular, so the peach and salmon colours are often heat-treated to reduce the orange tones.

These heat treatments are stable and as they cannot be distinguished from natural heating, they do not need to be disclosed.

However, many morganite ‘purists’ actually prefer the peach and salmon-coloured gemstones, as they know they have not been artificially heated.

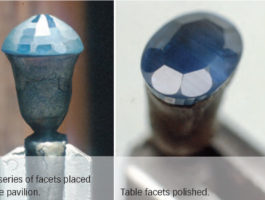

Often, the lighter coloured gemstones are cut with large pavilions to boost the intensity of the hue; this is an important point to note when designing morganite jewellery.

Morganite frequently occurs in much larger crystals than emerald and is often free from inclusions.

However, you occasionally may see multiphase inclusions that include a bubble! This kind of inclusion indicates a natural stone.

Morganite is also produced synthetically via the hydrothermal method. Here, one might notice the ‘hazy’ growth features typical of hydrothermally grown gems.

This feature is often observed through the gemstone’s pavilion, but not often seen when viewed through the crown.

It is essential to observe these visual features to confirm that the gemstone is synthetic, as comparing the refractive index can be unreliable.

That is because the refractive index range of synthetic morganite overlaps with the lower portion of the refractive index range of natural morganite.

If one is to embrace the spiritual side of crystal collectors, then morganite is a gemstone associated with the heart chakra.

Called the ‘stone of divine love’, it is said to bring healing, compassion, assurance and promise.

With its ‘gentle energy’, many believe morganite cleanses the mind of stress and anxiety, old wounds and hidden traumas, and kindles lightness within the spirit – something we could all use in these strange and uncertain times!

Kathryn Wyatt BSc FGAA Dip DT is a qualified gemmologist, diamond technologist, registered jewellery valuer, educator and member of the Australian Antique & Art Dealers Association.